What is Marfan syndrome?

Marfan syndrome is a heritable condition that affects the connective tissue. The primary purpose of connective tissue is to hold the body together and provide a framework for growth and development. In Marfan syndrome, the connective tissue is defective and does not act as it should. Because connective tissue is found throughout the body, the syndrome can affect many body systems, including the skeleton, eyes, heart and blood vessels, nervous system, skin, and lungs.

Who gets this syndrome?

Marfan syndrome affects men, women, and children, and has been found among people of all races and ethnic backgrounds.

What are the signs and symptoms?

It affects different people in different ways. Some people have only mild symptoms, while others are more severely affected. In most cases, the symptoms progress as the person ages. The body systems most often affected by the syndrome are:

- Skeleton. People with the syndrome are typically very tall, slender, and loose-jointed. Because Marfan syndrome affects the long bones of the skeleton, a person’s arms, legs, fingers, and toes may be disproportionately long in relation to the rest of the body. A person with the syndrome often has a long, narrow face, and the roof of the mouth may be arched, causing the teeth to be crowded. Other skeletal problems include a sternum (breastbone) that is either protruding or indented, curvature of the spine (scoliosis), and flat feet.

- Eyes. More than half of all people with the condition experience dislocation of one or both lenses of the eye. The lens may be slightly higher or lower than normal, and may be shifted off to one side. The dislocation may be minimal, or it may be pronounced and obvious. One serious complication that may occur with this disorder is retinal detachment. Many people with the condition are also nearsighted (myopic), and some can develop early glaucoma (high pressure within the eye) or cataracts (the eye’s lens loses its clearness).

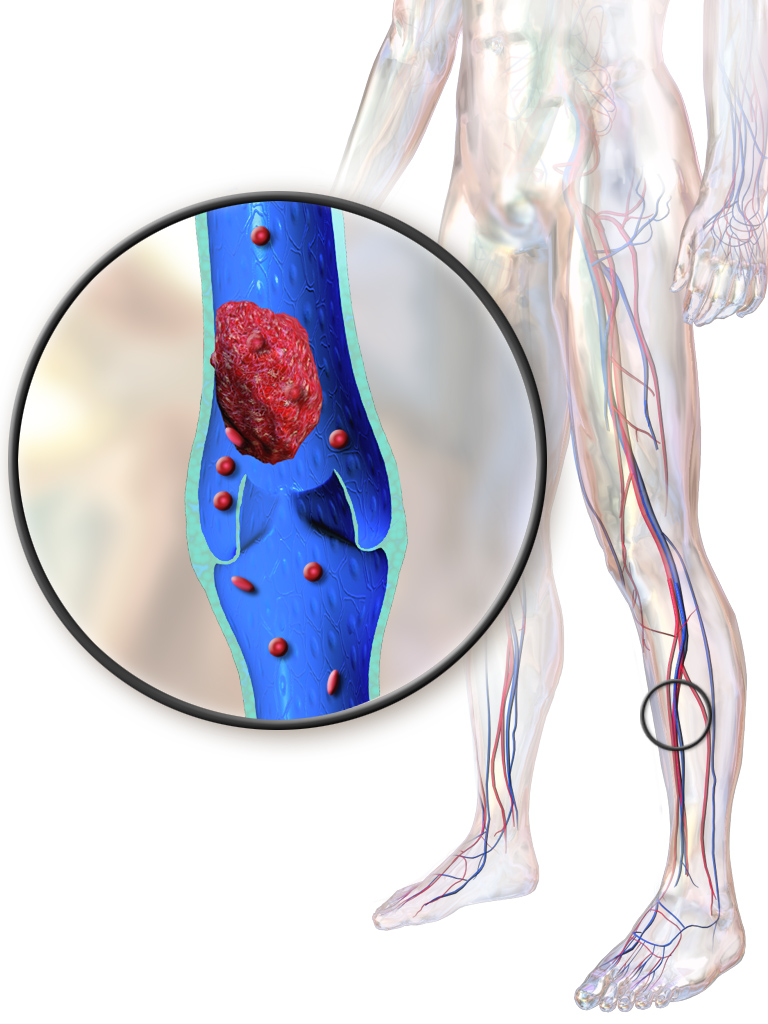

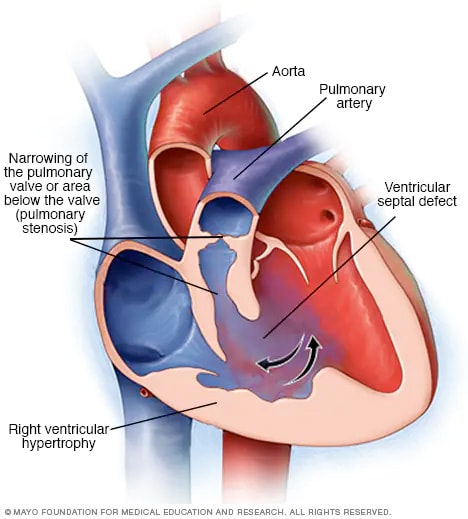

- Heart and blood vessels (cardiovascular system). Marfan syndrome patients have problems associated with the heart and blood vessels. Because of faulty connective tissue, the wall of the aorta (the large artery that carries blood from the heart to the rest of the body) may be weakened and stretch, a process called aortic dilatation. Aortic dilatation increases the risk that the aorta will tear (aortic dissection) or rupture, causing serious heart problems or sometimes sudden death. Sometimes, defects in heart valves can also cause problems. In some cases, certain valves may leak, creating a “heart murmur,” which a doctor can hear with a stethoscope. Small leaks may not result in any symptoms, but larger ones may cause shortness of breath, fatigue, and palpitations (a very fast or irregular heart rate).

- Nervous system. The brain and spinal cord are surrounded by fluid contained by a membrane called the dura, which is composed of connective tissue. Marfan syndrome patients grow older, the dura often weakens and stretches, then begins to weigh on the vertebrae in the lower spine and wear away the bone surrounding the spinal cord. This is called dural ectasia. These changes may cause only mild discomfort; or they may lead to radiated pain in the abdomen; or to pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs.

- Skin. Many people with Marfan syndrome develop stretch marks on their skin, even without any weight change. These stretch marks can occur at any age and pose no health risk. However, people with Marfan syndrome are also at increased risk for developing an abdominal or inguinal hernia, in which a bulge develops that contains part of the intestines.

- Lungs. Although connective tissue problems make the tiny air sacs within the lungs less elastic, people with Marfan syndrome generally do not experience noticeable problems with their lungs. If, however, these tiny air sacs become stretched or swollen, the risk of lung collapse may increase. Rarely, people with Marfan syndrome may have sleep-related breathing disorders such as snoring, or sleep apnea (which is characterized by brief periods when breathing stops).

Is Marfan syndrome genetic or inherited (causes)?

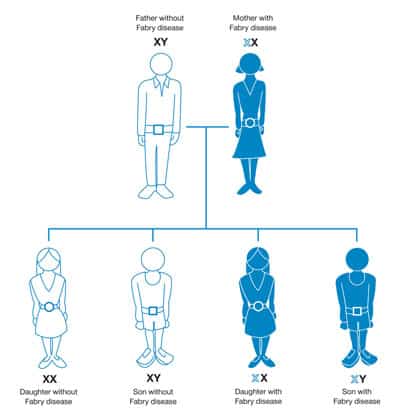

Caused by a defect, or mutation, in the gene that determines the structure of fibrillin-1, a protein that is an important part of connective tissue. A person with Marfan syndrome is born with the disorder, even though it may not be diagnosed until later in life.

The defective gene that causes Marfan syndrome can be inherited: The child of a person who has Marfan syndrome has a 50 percent chance of inheriting the disease. Sometimes a new gene defect occurs during the formation of sperm or egg cells, making it possible for two parents without the disease to have a child with the disease. But this is rare. Two unaffected parents have only a 1 in 10,000 chance of having a child with Marfan syndrome. Possibly 25 percent of cases are due to a spontaneous mutation at the time of conception.

Although everyone with Marfan syndrome has a defect in the same gene, different mutations are found in different families, and not everyone experiences the same characteristics to the same degree. In other words, the defective gene expresses itself in different ways in different people. This phenomena is known as variable expression. Scientists do not yet understand why variable expression occurs in people with Marfan syndrome.

How Is Marfan Syndrome Treated?

Marfan syndrome requires a treatment plan that is individualized to the patient’s needs. Some people need regular follow-up appointments with their doctor, and during the growth years, routine cardiovascular, eye, and orthopedic exams. Others may need medications or surgery. The approach depends on the structures affected and the severity:

Medications:

Medications are typically not used to treat Marfan syndrome. However, your doctor may prescribe a beta-blocker, which decreases the forcefulness of the heartbeat and the pressure within the arteries, thus preventing or slowing the enlargement of the aorta. Beta-blocker therapy is usually started when the person with Marfan syndrome is young.

Some people are unable to take beta-blockers because they have asthma or because of the medication’s side effects, which may include drowsiness or weakness, headaches, slowed heartbeat, swelling of the hands and feet or trouble breathing and sleeping. In these cases, another medication called a calcium channel blocker may be recommended.

Surgery:

The goal of surgery for Marfan syndrome is to prevent aortic dissection or rupture and to treat problems affecting the heart’s valves, which control the flow of blood in and out of the heart and between the heart’s chambers.

The decision to perform surgery is based on the size of the aorta, expected normal size of the aorta, rate of aortic growth, age, height, gender, and family history of aortic dissection. Surgery involves replacing the dilated portion of the aorta with a graft, a piece of man-made material that is inserted to replace the damaged or weak area of the blood vessel.

A leaky aortic or mitral valve (the valve that controls the flow of blood between the two left chambers of the heart) can damage the left ventricle (the lower chamber of the heart that is the main pumping chamber) or cause heart failure. In these cases, surgery to replace or repair the affected valve is necessary. If surgery is performed early, before the valves are damaged, the aortic or mitral valve may be repaired and preserved. If the valves are damaged, they may need to be replaced.

If surgery is needed, you should consult with a surgeon who is experienced in surgery for Marfan syndrome. People who have surgery for Marfan syndrome still require life-long follow-up care to prevent future complications associated with the disease.

How Does Marfan Sydrome Affect Lifestyle Choices?

- Activity. Most people with Marfan syndrome can participate in certain types of physical and/or recreational activities. Those with dilation of the aorta will be asked to avoid high intensity team sports, contact sports, and isometric exercises (such as weight lifting). Ask your cardiologist about activity guidelines for you.

- Pregnancy . Genetic counseling should be performed prior to pregnancy because Marfan syndrome is an inherited condition. Pregnant women with Marfan syndrome are also considered high-risk cases. If the aorta is normal size, the risk for dissection is lower, but not absent. Those with even slight enlargement are at higher risk and the stress of pregnancy may cause more rapid dilation. Careful follow-up, with frequent blood pressure checks and monthly echocardiograms is required during pregnancy. If there is rapid enlargement or aortic regurgitation, bed rest may be required. Your doctor will discuss with you the best method of delivery with you.

- Endocarditis prevention. People with Marfan syndrome who have heart or valve involvement or who have had heart surgery may be at increased risk for bacterial endocarditis. This is an infection of the heart valves or tissue which occurs when bacteria enters the blood stream. To prevent this, antibiotics may be needed prior to dental or surgical procedures. Ask your doctor whether you need antibiotics, and if so, how much and what kind should be taken. A wallet card may be obtained from the American Heart Association with specific antibiotic guidelines.

- Emotional considerations. Learning you have Marfan syndrome may cause you to feel angry, frightened or sad. You may need to make changes in your lifestyle and adjust to having careful medical follow-up the rest of your life. You may have financial concerns. You also need to consider the risk to your future children. The National Marfan Foundation can provide support.