Thrombophilia is a condition where the blood has an increased tendency to form clots. Blood clots can cause problems such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism. There are different types of thrombophilia – some are inherited and some are acquired, meaning they usually develop in adult life. Often thrombophilia is mild. Many people with thrombophilia do not have problems from their condition. Blood tests can diagnose the problem. Thrombophilia does not always require treatment but some people need to take aspirin or warfarin. If you have thrombophilia, be aware of the symptoms of a blood clot and get treatment immediately if you have symptoms.

What is thrombophilia?

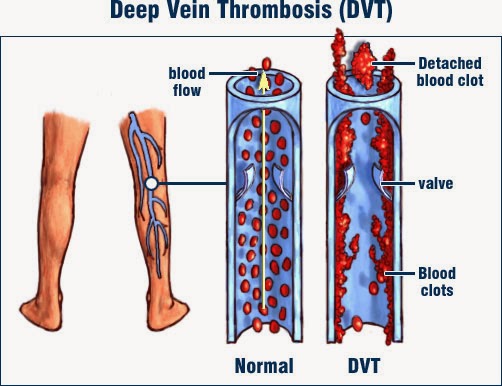

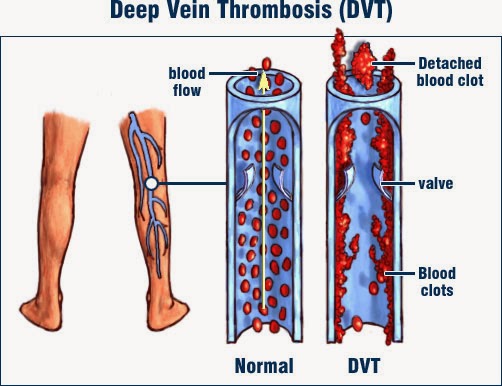

Thrombophilia refers to a groups of conditions where the blood clots more easily than normal. This can lead to unwanted blood clots (called thromboses) forming within blood vessels. These blood clots can cause problems such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism. See separate leaflets called Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism for more details.

What causes thrombophilia?

The body has a natural clotting process in the blood, which is altered in thrombophilia.

The normal clotting process is called haemostasis. It helps to stop bleeding if you have an injury such as a cut. When a blood vessel is injured, the clotting process is triggered. This is called the clotting cascade. It is a chain reaction of different chemicals in the blood which are called clotting factors. The clotting cascade makes the blood solidify into a clot, which sticks to the injured part of the blood vessel. Small particles in the blood, called platelets, also help to form the clot.

There are also natural chemicals in the blood which act against the clotting system, to stop the blood clotting too much.

Thrombophilia occurs if the normal balance of the clotting system is upset. There may be too much of a clotting factor, or too little of a substance that opposes clotting.

Thrombophilia can cause unwanted blood clots (thromboses). This does not mean that every person with thrombophilia will develop a blood clot. But, it means that you have a higher risk than normal of having clots. The extra risk will depend on the type of thrombophilia that you have.

What is a thrombosis?

A blood clot that forms within a blood vessel is known medically as a thrombus. Thrombosis is the process that occurs to form a thrombus. A thrombus can block a blood vessel – this blockage is now also known as a thrombosis. Thromboses is the plural version of thrombosis (that is, more than one).

What are the different types of thrombophilia?

Thrombophilias can be classified into inherited or acquired. The inherited ones are genetic and may be passed on from parent to child.

Acquired thrombophilias are not inherited, meaning they have nothing to do with your genes. Usually, acquired thrombophilias become apparent in adulthood. They can happen as a result of other medical problems that have developed, or they might be due to problems with the immune system.

It is possible to have a mixed thrombophilia, due partly to genetic and partly to non-genetic factors.

The different types of thrombophilia are explained in more detail later in this leaflet.

What are the symptoms of thrombophilia?

There are no symptoms unless the thrombophilia results in a blood clot (thrombosis).

Many people with thrombophilia do not develop a blood clot and have no symptoms at all.

What are the symptoms of blood clots?

Blood clots can form in arteries and veins. Arteries are blood vessels that take blood away from the heart to the organs and tissues of the body. Veins are blood vessels that bring blood back to the heart, from the rest of the body.

A blood clot in a vein is the most common problem with thrombophilia – this is called venous thrombosis. Possible symptoms are:

- Pain and swelling in a leg. This occurs if you have a blood clot in a large vein in a leg. This is commonly known as a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). A DVT can occur in any vein in your body but most often affects a leg vein.

- The blood clot may travel to the heart and on into a lung, causing a pulmonary embolism. Possible symptoms are chest pain, pain on deep breathing, shortness of breath or, rarely, collapse.

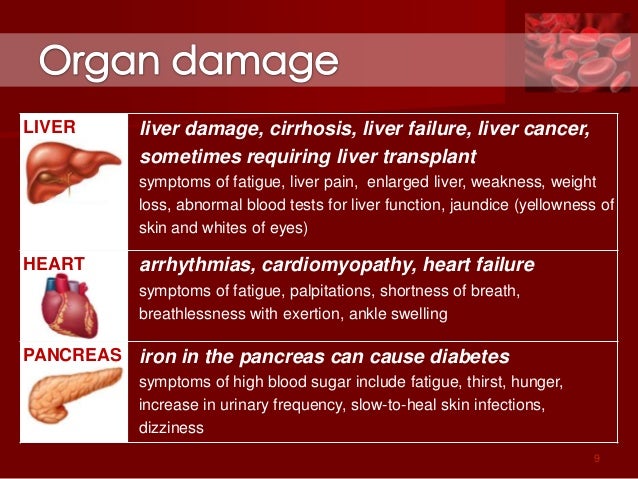

- Some types of thrombophilia can cause a blood clot in an unusual site such as the brain, gut or liver. This can cause symptoms in the head or the tummy (abdomen). A blood clot in the liver veins is called Budd-Chiari syndrome.

A blood clot in an artery can occur with some types of thrombophilia. This is called arterial thrombosis. Depending on which artery is affected, a blood clot in an artery can cause a stroke, a heart attack or problems with the placenta during pregnancy. So the possible symptoms of arterial thrombosis due to thrombophilia are:

- Having a stroke at a relatively young age.

- Repeated miscarriages.

- Pregnancy problems: pre-eclampsia, reduced fetal growth or, rarely, fetal death (a stillbirth, or intrauterine death).

- A heart attack.

It is important to remember that all of these conditions can be due to causes other than thrombophilia. For example, smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol are the main risk factors for developing problems such as heart attack and stroke.

For this reason, not everyone with a stroke or heart attack is tested for thrombophilia, as it is not a common cause.

What are the tests for thrombophilia?

Thrombophilia is diagnosed by blood tests.

Tests are done some weeks or months after having a DVT or pulmonary embolism, as the presence of these conditions can affect the results. Usually you have to wait until you have been off blood-thinning medication (anticoagulants), such as warfarin, for 4-6 weeks. If you have recently been pregnant, the tests may have to be delayed by eight weeks. This is because the results in pregnancy can be much harder to understand.

A sample of blood is taken and a number of different tests will be done on it, to check different parts of the clotting process. Usually, the tests are done in two stages. The first test is a thrombophilia screen which is some basic clotting tests. If the results of this suggest that thrombophilia is possible then another blood sample will be taken for more detailed tests.

You may be referred to a doctor specialising in blood conditions (a haematologist). The doctor will usually ask about your history and family history. This will help with interpreting the test results.

What is the treatment for thrombophilia?

The first step is for you and your doctor to consider how much risk there is of you developing a blood clot. This risk depends on a combination of things, such as:

- What type of thrombophilia you have (some are more high-risk for blood clot than others).

- Your age, weight, lifestyle and other medical conditions.

- Whether you are pregnant or have recently given birth.

- Whether you have already had a blood clot.

- Your family history – whether any close relatives have had a blood clot.

This information will help your doctor to assess how much risk you have of developing a blood clot and what type of blood clot could occur. Then you and your doctor can discuss the pros and cons of taking treatment and, if needed, what type of treatment to take.

Possible treatments for thrombophilia are:

Low-dose aspirin

Low-dose aspirin inhibits the action of platelets, so can help to prevent blood clots. It may also help prevent miscarriage or pregnancy problems, in some types of thrombophilia.

Anticoagulant treatment

Anticoagulation is often called thinning the blood. However, it does not actually thin the blood. It alters certain chemicals in the blood to stop blood clots forming so easily – in effect, it slows down the clotting process. It doesn’t dissolve a blood clot either (as some people incorrectly think). The body’s own healing mechanisms can then get to work to break up any existing blood clot.

Anticoagulation can greatly reduce the chance of a blood clot from forming. Anticoagulant medication is commonly used to treat a venous thrombosis (such as a DVT) or a pulmonary embolism.

In thrombophilia, anticoagulant medication may be advised if:

- You have had a blood clot, to prevent another one.

- You have not had a blood clot but have a high risk of developing one.

- You have a temporary situation that puts you at high risk of a blood clot. This may be the case if you are pregnant, within six weeks after childbirth, or are immobile for a long period.

Anticoagulant medicines are either given by injection (eg, heparin) or can be taken as a tablet. Warfarin is the most commonly used tablet anticoagulant medicine. Other anticoagulants taken in tablet form include apixaban, edoxaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Warfarin is the usual anticoagulant. However, it takes a few days for warfarin tablets to work fully. Therefore, heparin injections (often given just under the skin) are used alongside warfarin in the first few days (usually five days) for immediate effect if you currently have a blood clot. If you are starting warfarin and don’t have a blood clot (that is, it is just to prevent one), you won’t need heparin injections first.

The aim is to get the dose of warfarin just right so the blood will not clot easily. Too much warfarin may cause bleeding problems. To get the dose right, you will need a regular blood test, called International Normalised Ratio (INR), whilst you take warfarin. The dose is adjusted on an individual basis according to the result of this blood test. The INR is a blood test that measures your blood clotting ability. You need the tests quite often at first but then less frequently once the correct dose is found.

An INR of 2.5 is usually the aim if you take warfarin to prevent a blood clot in thrombophilia or to treat a DVT or pulmonary embolism. However, anywhere in the range 2-3 is usually OK. If you have had recurrent DVTs, or have had a pulmonary embolism whilst on warfarin, you might need a higher INR (even ‘thinner’ blood). INR blood tests can usually be done in an outpatient clinic, or sometimes by your GP. You may be advised to take warfarin on a lifelong basis to prevent blood clots if you have thrombophilia. Or, you may have short-term treatment for your current DVT or pulmonary embolism (usually 3-6 months).

Heparin is an injectable anticoagulant. Standard heparin is given intravenously (IV), which means directly into a vein – usually in the arm. This type of heparin is given in hospital and monitored with blood tests.

Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is injected into the skin on the lower tummy (abdomen). It can be given at home, either by a district nurse, or you can be taught to self-inject (or a carer can do it for you). It does not need blood tests to monitor it. Different doses are used for prevention (prophylaxis) and treatment of an existing blood clot. There are different brands of heparin injection; the common ones you might see used are Clexane® and Fragmin®.

Treatment in pregnancy

If you are pregnant or planning a pregnancy, discuss this with your doctor, and tell your midwife and doctor specialising in pregnancy and childbirth (obstetrician) about the thrombophilia. Treatment for thrombophilia may be different in pregnancy because:

- Some women with certain types of thrombophilia are advised to take low-dose aspirin while pregnant, to help prevent miscarriage or pregnancy problems.

- The pregnancy itself increases the risk of a venous thrombosis – this applies to the whole pregnancy and especially to the six weeks after childbirth. So you may be advised to start anticoagulant treatment while pregnant or after childbirth. This will depend on the type of thrombophilia and your medical history.

- If you were taking warfarin, you will normally be advised to change to heparin instead. This is because heparin is safer for the unborn baby (there is a significant chance that warfarin could cause fetal abnormalities). Both heparin and warfarin are safe for breast-feeding.

Prevention of DVT

Certain situations can temporarily put you at high risk of having a blood clot, and in these situations you may be advised to take extra treatment for a while. Examples are pregnancy and after childbirth, severe illness, major surgery, or anything which immobilises you, such as travel or an operation. Special stockings such as flight socks or compression stockings may also be advised to help prevent a DVT.

General advice for people with thrombophilia

- If you are having any medical treatment or surgery, tell your doctor/nurse/pharmacist about the thrombophilia.

- Be aware of the warning symptoms of a blood clot – obtain medical help immediately if you suspect one (see above for symptoms).

- Avoid lack of fluid in the body (dehydration) by drinking adequate amounts of fluid. Dehydration can contribute to blood clots forming.

- Keep active, and avoid being immobile for long periods – immobility helps cause blood clots in the legs (DVTs).

- Caution with medication: some medications increase the risk of a blood clot. For example, the combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill or patch and hormone replacement therapy (HRT). You may be advised to avoid certain medications, or to change to one which does not affect blood clotting.

- Keep to a healthy weight – being overweight or obese increases the risk of blood clots in legs.

- To keep blood vessels healthy (arteries in particular), do not smoke. This is important if you have thrombophilia of a type that can cause blood clots in arteries, as smoking also promotes arterial blood clots.

![[genetic test]](http://cdn1.medicalnewstoday.com/content/images/articles/166/166455/genetic-test.jpg)

![[Woman fainting]](http://cdn1.medicalnewstoday.com/content/images/articles/182/182524/woman-fainting.jpg)